Gen Z workers say they’re open to jobs in manufacturing. But getting them to take these jobs, engage, and stay will mean changing a work environment long optimized for machines, not people.

In some respects, the US manufacturing sector would seem to be in better shape than it’s been in years. Unprecedented levels of funding are flowing in from both domestic and foreign sources. A surge of new technologies, collectively promising a Fourth Industrial Revolution, is taking hold—and promising to reignite productivity growth. And, conveniently, a generation of workers who have spent their whole lives immersed in technology is coming on the scene: Generation Z.

In contrast to older generations, more of Gen Z say they’re open to the idea of working in manufacturing. But ask a plant manager in Ohio or Nevada looking for entry-level workers to staff a technologically advanced assembly line and you’ll likely hear frustration. What seems to them like a great opportunity for starting a career isn’t attracting very many Gen Z applicants. And those who get hired often don’t stay for long, prompting a fundamental question: What do these workers want?

Our research confirms what these managers are experiencing firsthand: not nearly enough Gen Z workers are entering the field to fill factory vacancies (see sidebar, “About the research”). Once there, Gen Z engagement levels tend to be low, and they’re more likely to leave than older workers.

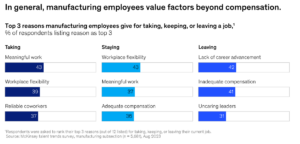

According to the research, Gen Z workers’ motivations for taking, keeping, or leaving a job are similar to those of older cohorts, although compensation is somewhat less of a draw compared with factors such as career development and advancement, flexibility, meaningful work, and caring leadership (Exhibit 1). Another big difference, of course, is that Gen Z knows it has options, given sustained low employment.

What manufacturers are “doing wrong” with Gen Z employees is just a symptom of what they have been doing with their employees more generally, often for decades. Their standard move was to offer more money. But even when that option has been affordable, it clearly isn’t working: manufacturers are filling only six out of ten job openings.

A few companies are getting it right by applying an old insight: regarding workers as critical investments, not just as costs. One consumer goods manufacturer restructured its workforce management system to offer greater flexibility and give workers more control over their career pathways. Both factors are critical for Gen Z and are important for other workers, too. The impact was profound: staffing levels rose 25 percentage points, raising production output by 20 percent as losses due to unscheduled line shutdowns fell by 70 percent.

How Gen Z differs from other worker cohorts

Achieving those sorts of results is possible only when companies understand what workers are looking for from a job and develop a strategy to meet those needs within the broader operational goals of the organization. Our research sought to identify differences between generations in deciding to take a job, stay in a job, or quit. In most respects, Gen Z’s preferences resemble those of older workers. But three differences stand out.

Money matters for Gen Z, but less than for older workers. Compensation is the number-one factor for boomers considering taking a job, and then falls steadily in importance among Gen X, older millennials, and younger millennials. For Gen Z, compensation places only sixth in importance. Likewise, for staying in a job, compensation is a top two factor for older workers but tumbles to eighth place for Gen Z. For leaving a job, compensation is a top two factor among all ages—except for Gen Z, which ranks it third, behind concerns about advancement and meaning in their work.

Security and respect matter for Gen Z. For staying in a job, Gen Z was the only cohort that listed physical and psychological safety—meaning security in their physical environment and a respect for their contributions—as a top three factor. No other cohort had it in the top five. Specifically, Gen Z wants to know that they can make mistakes, learn, and still have a chance to develop their skills for long-term career growth. It therefore may be especially important for manufacturers to shift mindsets and behaviors—particularly at the shop floor supervisor level—to convince Gen Z to stay.

Even more than other workers, Gen Z wants to make a difference. They’re the only cohort that considers “meaning” as a top two reason to take, keep, or quit a job (Exhibit 2). Only younger millennials came close.

Gen Z’s employment experiences also reflect broader societal and economic changes. For example, Gen Zers are the second-most-active participants in gig work, after millennials. Partly as a result, Gen Z’s overall workforce participation rate is at least four percentage points lower than that of millennials or Gen X when those groups were the same age, with higher education accounting for another portion of the gap. Record-high levels of start-up formation, a pandemic-era surge that has only just started to slow, may also have absorbed some Gen Z talent.

Arguably the most important macroeconomic difference between Gen Z workers and their millennial and Gen X predecessors, however, is that they have entered the workforce at a time of unusually high labor demand. Since 1970, the annual US unemployment rate has averaged below 4 percent for only four years (2018, 2019, 2022, and 2023)—all of them since 2015, the year the oldest Gen Z members turned 18.1 These differences are already playing out in how Gen Z behaves in the job market.

Earning Gen Z’s interest (and loyalty)

Manufacturing is currently struggling to find enough workers to meet demand. Although production, supervisor, and managerial employment numbers have recovered to or beyond pre-COVID-19 levels, churn in the workforce is high. Since January 2020, the manufacturing sector has experienced a 43 percent gap between the number of job openings and hires.

The new laws of attraction: Flexibility, connectivity, and meaning

With so many workers leaving manufacturing, attracting replacements has become critical for the health of the entire sector. But so far, too few Gen Z workers are staying on factory floors. Instead, since 2019, Gen Z’s share of the manufacturing workforce has declined (to 7 from 8 percent), even though more than 20 million Gen Zers reached adulthood in the intervening years. Conversely, older workers’ share of the total has risen by about three percentage points, to 26.5 from 23.6 percent.

Manufacturers often have responded to past labor shortages with wage increases, and indeed, since January 2020 manufacturing wages have risen by a cumulative 21.5 percent. It hasn’t been enough.

And even if employers could afford substantial wage increases, it’s not clear that they would attract Gen Z. Contrary to prior generations and stereotypes, Gen Z workers are taking jobs less for compensation and more because of factors including their relationships with coworkers (43 percent), the chance to do meaningful work (41 percent), and workplace flexibility (38 percent).

At least one US food manufacturer has targeted the third factor, upending long-standing views that emphasized efficient operation of equipment over worker experience. After full-time line operator openings remained unfilled for months, company leaders finally recognized that solutions would require a radical reassessment of assumptions—starting with the rigid 12-hour shift. Designed to keep machines humming 24 hours a day, the shifts could be supported so long as enough workers were available to design their days around the demands of the job. But shrinking populations meant that too few workers could meet that requirement. Surveyed workers at the consumer goods manufacturer, for example, listed “schedule” as the number two reason for why they would quit.

Instead, reaching new workers meant restructuring jobs wherever possible so that they no longer had to be performed for 12 continuous hours. The company found that certain packaging roles, for example, could be performed by groups of workers at any time. Switching those jobs from full-time to part-time, and letting employees opt in to shifts based on their availability, led to dozens of applications. Employees who want even more staffing options can cross-train for different roles, giving the company additional backup.

Increasing engagement: Capability building and technology

Once manufacturing organizations have managed to attract Gen Z workers, the next step is to engage them so they can be successful. Many leaders report that early-career workers seem to lack technical or people skills that traditionally have been viewed as fundamental. While there’s some basis for this view, it often ignores the skills that Gen Z does have but that many manufacturing environments aren’t yet equipped to use well.

For example, having grown up with instant access to digital answers, Gen Zers are more likely than older workers to look first to self-help videos to solve problems. That habit can yield fast, accurate answers—if the solutions make sense for the shop floor where they work. But the average Gen Z worker is likely somewhat less experienced (and perhaps less comfortable) with asking coworkers for advice in person.

Manufacturers will need to merge the digital and the analog in ways that give workers the skill development they need—and quickly—while ensuring that they are building interpersonal relationships with experienced workers and supervisors who can help integrate them in the community. Otherwise, younger workers can become disengaged, resulting in higher rates of absenteeism and lower productivity. McKinsey’s talent trends research2 has found that about three in five Gen Z workers in manufacturing are disengaged, which is comparable to the total number of disengaged workers of all ages outside of manufacturing. We estimate that this level of disengagement costs US manufacturers about $20 billion to $40 billion per year.